Birds to Break your Heart

Julius is a young Nigerian-German man who lives in New York City. He is the central character of the novel Open City by Teju Cole. Julius likes to watch birds. Here’s what passes through his mind as he watches sparrows flit through the bare branches of a tree outside a friend’s apartment on Amsterdam Ave:

As I reflected on the fact that in each of these creatures was a tiny red heart, an engine that without fail provided the means for its exhilarating midair maneuvers, I was reminded of how often people took comfort, whether consciously or not, in the idea that God himself attended to these homeless travelers with something like personal care; that contrary to the evidence of natural history, he protected each one of them from hunger and hazard and the elements.

Julius takes long walks through the city and often finds himself in conversation with strangers. A Haitian shoe-shiner tells him about raising his orphaned niece and founding a school for orphaned children in New York. A jailed refugee from Liberia recounts his journey through peril and hunger to the United States. In each of these people is a red heart, and in hearing their stories we grow to love them and hope for their protection.

Julius takes long walks through the city and often finds himself in conversation with strangers. A Haitian shoe-shiner tells him about raising his orphaned niece and founding a school for orphaned children in New York. A jailed refugee from Liberia recounts his journey through peril and hunger to the United States. In each of these people is a red heart, and in hearing their stories we grow to love them and hope for their protection.

Julius is enormously erudite and frames his world in terms of art, classical music, and literature. Many readers, being readers, will empathize with him. And for Julius art is almost always bound up with empathy. An exhibit of John Brewster paintings sends him into a reverie, contemplating disabled people’s place in society. At a photography exhibit, he watches a Hasidic couple looking at a photo of Goebbels and, overwhelmed, needs to return home. During his college literature professor’s last days, Julius visits and reads out loud to the elderly man.

All of these briefly-glimpsed characters and works of art add up to a mosaic. Teju Cole explained his book’s structure in an interview with 3:AM magazine:

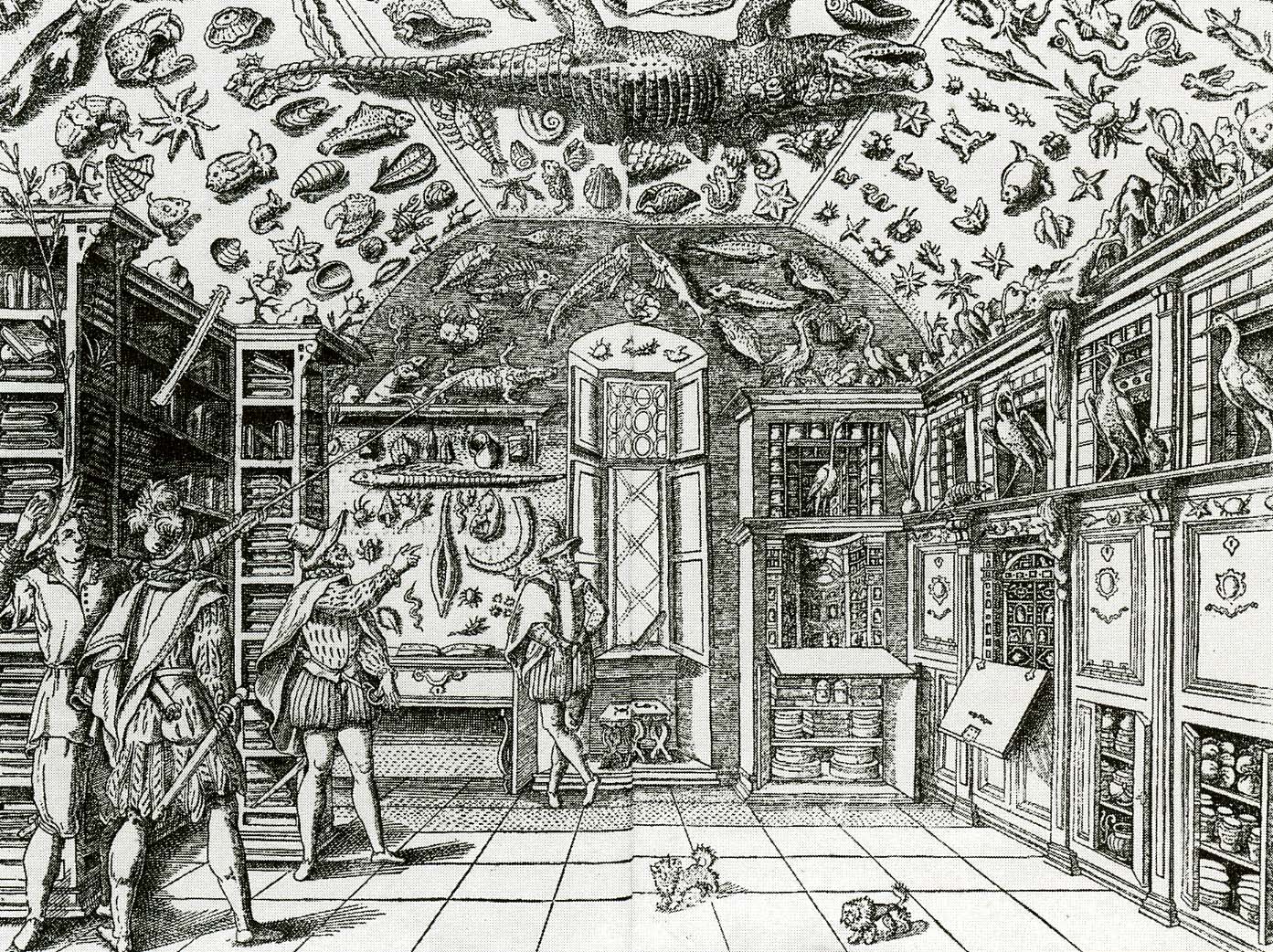

TC: In a sense, Open City is a kind of Wunderkammer, one of those little rooms assembled with bric-a-brac by Renaissance scholars. I don’t mean it as a term of praise: these cabinets of curiosities contained specific sorts of objects — maps, skulls (as memento mori), works of art, stuffed animals, natural history samples, and books — and Open City actually contains many of the same sort of objects.

Warning: Spoilers and pessimism ahead.

Near the end of the book, a woman who knew Julius years ago in Nigeria tells him that he once raped her at a party, a rape that he apparently does not remember. This is a painful and dissonant fact. Julius does not react to the accusation. He gets up and leaves. A few pages later, Julius goes to the opera and afterwards locks himself out on the fire escape by accident.

The slick wirework was all that separated me from the street level of the city, some seventy feet down. The lights directly below were visible beneath my feet, and my head and coat were already wet. My fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight.

Cole has flipped the metaphor. In the beginning of the novel we flew through the city with Julius. Now we feel a callous kind of indifference to him. Does he deserve to be saved? Do we cheer for him to make it down the fire escape unharmed? It’s impossible to root for the book’s central character knowing the full story of his past.

Some commenters have dismissed the rape. Miguel Syjuco in the New York Times: “set against the novel’s grand scope, it feels unnecessary, either a misstep by a young author or an overstep by a persuasive editor.” James Wood wrote 3,262 words in the New Yorker about Open City and didn’t once mention it once.

This is a big mistake. Open City is meant to introduce a questioning note into the way we think about cities, strangers, and empathy.

This is a big mistake. Open City is meant to introduce a questioning note into the way we think about cities, strangers, and empathy.

From a distance, every member of the flock deserves love and protection. Told once, every stranger’s story is beautiful, and might well be true. Loving a stranger is easy. But digging deeper complicates the picture. You may strike lies, self-deception, cruelty. Cole is reminding us that cities — and by extension, globalization and technology — have cold rivers flowing beneath their warm bustle.

This is not a comfortable way to think about the people we pass on the street. But don’t open the Wunderkammer unless you want to be made uncomfortable.